How to Copy Vintage Millwork

Dixon Kerr is President of Old House Authority.

Dixon Kerr is President of Old House Authority.by Dixon Kerr

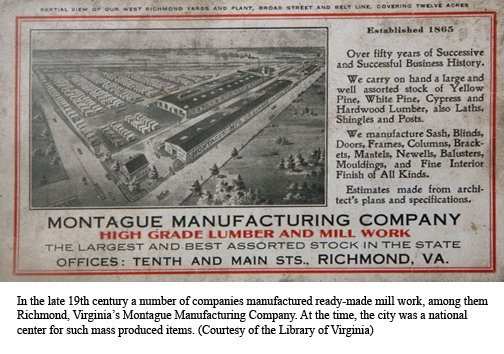

Living in a city that is graced with many houses and commercial buildings that were constructed throughout the last two centuries, I am often called on to make mill work that either completes a broken pattern or is a facsimile of a nearby one. I had done this many times when by chance I discovered a vintage mill work catalogue that featured pieces on houses identical to some I had recently made copies of. This began a search for more vintage catalogues of mill work companies in Richmond, Virginia, the city in which I live. What was revealed was not only a catalogue featuring scale drawings of many architectural objects that could be found in houses all around town but also the discovery that Richmond was an area prominent in the manufacture of mill work sold throughout the United States. In the late 1880s there were approximately a dozen such businesses in Richmond with thirty to fifty employees: Thomas E. Stagg, at 1421 Cary St.; J.J. Montague, at the corner of Ninth & Arch Streets; Hare and Tucker, at 2318 Main St.; Whitehurst and Owen, at Byrd & Tenth Streets; DuVal & Robertson, at 11th & Porter and 7th & Hull Streets; and Binswanger & Company, at 1427 E. Main St. Binswanger, now a commercial glass company, is still in business; Siewer's Lumber Company and Ruffin and Payne, still in business, were also in business at the time. Beckstoffer & Son continued in the business until the early twenty-first century.

I soon realized that having original salvaged pieces and the scale drawings from the vintage catalogues combined to create an important tool for preservation, restoration and architectural history because with such knowledge exact size patterns could be reproduced and used where they are indeed original to their style and time. All the catalogues I found and most of the ones I studied from other areas of the United States and Canada were entitled "Sash, Doors and Blinds."

Similarities among mill work manufacturers of the day did not occur by chance. There had long been a need for standardization of size and grade in the flourishing wood manufacturing business at the close of the nineteenth century. Molding, flooring, doors, windows--almost every item in a new house--was being made from the abundant supply of wood being harvested in the United States. A supplier in one city needed to be able to produce dimensional material that was compatible with similar needs elsewhere.

Some companies issued their catalogues in pocket size form, presumably for use on the job site.

Some companies issued their catalogues in pocket size form, presumably for use on the job site.These concerns were addressed at the Centennial Exhibition of 1876 in Chicago, and many standards in the industry resulted. These changes were reflected in the catalogues of many large manufacturers after that time, since they identified their catalogues as "universal" moldings books, or "universal " catalogues of various specialties. Manufacturers could now sell to wholesalers and wholesalers to retailers. Specialties such as brackets and balusters were included in these catalogues, but now their vernacular designs were marketed on a much broader level.

According to John Mass in The Glorious Enterprise: The Centennial of 1876, the Centennial demonstrated the worldwide integration of the academic and popular arts. A sameness in America's architectural character often today attributed to fast food franchises and motel chains is already evident in the 1870s. With the prefabrication of ornament, architecture became increasingly an art of assemblage, according to A. J. Bicknell in his Victorian Village Builder: an Architectural Guide of 1872.

According to Bicknell, "A flourishing trade in the manufacture and sale of wooden adornment began during the Victorian Era, when many of the items such as brackets and scrolled work of all sorts were conveniently categorized as ?gingerbread.?" There were many versions of how this came to be, but according to John Mass in The Golden Age; a View of Victorian America, this term precedes the Victorian era "when Gothic was translated into "Carpenter Gothic," the stone tracery became wooden gingerbread." This word is not of recent coinage or American origin. It dates to the medieval French ?ginginbrat" which meant preserved ginger. The last syllable was mistranslated into English as "bread," English gingerbread was a sort of cake, flavored with ginger and cut into fancy shapes. The word was then applied to the carved and gilded decoration of a sailing ship and finally to gaudy architectural ornament. It was first used in this sense in eighteenth century England.

The erroneous theory has been advanced that American gingerbread houses were copied from Swiss chalets, but this is highly unlikely because few, if indeed any, nineteenth century American carpenters took study trips to Switzerland. Moreover, few, if any, owned books on Swiss architecture. There are many thousands of gingerbread patterns varying in form from county to county, from town to town. When did they come from? The architectural pattern books contained only a few drawings of brackets. In actuality, local carpenters and lumber mills worked out their own fanciful gingerbread designs.

Gingerbread is part of the universal design language of the nineteenth century. The very same scrolls and curlicues are found in Victorian ironwork, in the patterns for Victorian needlework and dressmaking, in the Victorian printers' fancy typography and ornament, in the Victorians' "Spencerian" handwriting and flourishes. Houses aren't built in a vacuum.

Their origins and evolution aside, the mill work as presented by these patterns is an essential architectural element of period houses, and their faithful reproduction is a requirement for restoration.

Often during a restoration there are pieces missing that must be replicated. A broken or missing corbel must be repaired or replaced, or perhaps ventilator covers or similar items are missing or broken. In order to keep a series intact or when a number of houses all have a common vernacular theme, one must be able to reproduce original mill work.

To copy a piece such as a scrolled ventilator cover, for example, I first trace a paper pattern from the original piece. This process is the same for any item being made. A corbel, for instance, is just a series of separate pieces cut out and joined together.

Using a piece of parchment paper, available in the baking department of most grocery stores, cut a piece large enough to cover the original you wish to trace. Using a spray adhesive, lightly coat the paper pattern and wait three to five minutes, then position the paper on the wood. This makes a temporary bond that can later be peeled off. Be sure to work the air pockets out to the edge with your fingers.

Using a lead pencil, rub the point back and forth lightly along all the scrolled edges. A dark pattern line will become apparent, which becomes the pattern of the piece to be copied.

Next, cut a piece of 1/8" Baltic plywood to the same size as the original you wish to copy. Carefully peel the parchment paper pattern from the original, spray once more with adhesive, and glue it to the plywood.

Drill a small hole through each piece that is to be cut out, then insert the scroll saw blade into the hole and make the cut. When they are all done, lightly file or sand the edges smooth. This is the template, and it can be used repeatedly to mark stock that is to be cut out. Because the template is made from 1/8" stock, a pencil can be used to mark most of the lines. If a curve is too tight for a pencil, a scratch awl or knife can be used.